Hemingway wrote standing, Nabokov on index cards, Twain while puffing cigars, and Sitwell in an open coffin.

“We are spinning our own fates, good or evil, and never to be undone,” the William James’s famous words on habit echo. “Every smallest stroke of virtue or of vice leaves its never so little scar.”

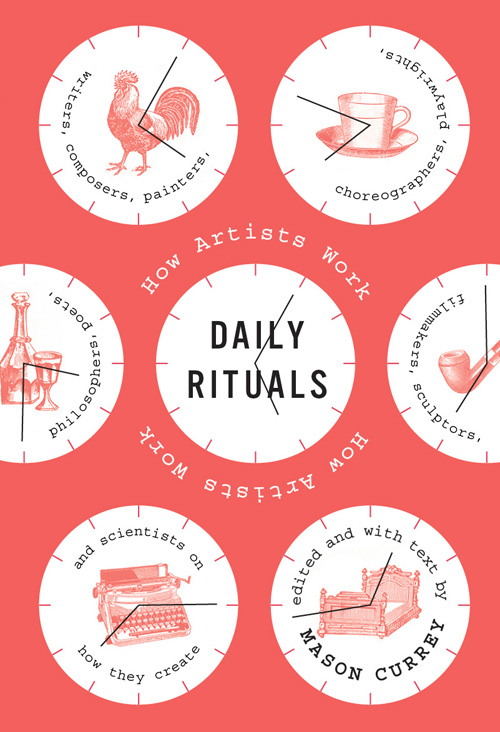

“We are spinning our own fates, good or evil, and never to be undone,” the William James’s famous words on habit echo. “Every smallest stroke of virtue or of vice leaves its never so little scar.”Given this omnibus of the daily routines of famous writers was not only one of my favorite articles to research but also the most-read and -shared one in the entire history of Brain Pickings, imagine my delight at the release of Daily Rituals: How Artists Work (public library) by Mason Currey, based on his blog of the same title. Currey, who culled the famous routines from a formidable array of interviews, diaries, letters, and magazine profiles, writes in the introduction:

Nearly every weekday morning for a year and a half, I got up at 5:30, brushed my teeth, made a cup of coffee, and sat down to write about how some of the greatest minds of the past four hundred years approached this exact same task — that is, how they made the time each day to do their best work, how they organized their schedules in order to be creative and productive. By writing about the admittedly mundane details of my subjects’ daily lives — when they slept and ate and worked and worried — I hoped to provide a novel angle on their personalities and careers, to sketch entertaining, small-bore portraits of the artist as a creature of habit.The notion that if only we could replicate the routines of great minds, we’d be able to reverse-engineer their genius is, of course, an absurd one — yet an alluring one nonetheless. Currey’s feat is in at once indulging and debunking the mythology of our voyeuristic routine-fetishism by exploring the wildly diverse ways in which celebrated creators structure their days, while at the same time engaging in delicate pattern-recognition to reveal a number of recurring undercurrents essential for creative success. Here is a small sampling of some favorites:

Mark Twain — master of epistolary snark, unsuspected poet, cheeky adviser of little girls — followed a simple but rigorous routine:

He would go to the study in the morning after a hearty breakfast and stay there until dinner at about 5:00. Since he skipped lunch, and since his family would not venture near the study — they would blow a horn if they needed him — —he could usually work uninterruptedly for several hours. … After dinner, Twain would read his day’s work to the assembled family. He liked to have an audience, and his evening performances almost always won their approval. On Sundays, Twain skipped work to relax with his wife and children, read, and daydream in some shady spot on the farm. Whether or not he was working, he smoked cigars constantly.In 1941, six years after illustrating James Joyce’s Ulysses, Henri Matisse told a visitor to his studio that he was never bored. He explained:

Do you understand now why I am never bored? For over fifty years I have not stopped working for an instant. From nine o’clock to noon, first sitting. I have lunch. Then I have a little nap and take up my brushes again at two in the afternoon until the evening. You won’t believe me. On Sundays, I have to tell all sorts of tales to the models. I promise them that it’s the last time I will ever beg them to come and pose on that day. Naturally I pay them double. Finally, when I sense that they are not convinced, I promise them a day off during the week. “But Monsieur Matisse,” one of them answered me, “this has been going on for months and I have never had one afternoon off.” Poor things! They don’t understand. Nevertheless I can’t sacrifice my Sundays for them merely because they have boyfriends.

Gertrude Stein’s routine relied heavily on her partner, Alice B. Toklas, who all but managed Stein’s life:

Miss Stein gets up every morning about ten and drinks some coffee, against her will. She’s always been nervous about becoming nervous and she thought coffee would make her nervous, but her doctor prescribed it. Miss Toklas, her companion, gets up at six and starts dusting and fussing around. . . . Every morning Miss Toklas bathes and combs their French poodle, Basket, and brushes its teeth. It has its own toothbrush.

Contrary to common legend, Hemingway, a proponent of creative solitude, didn’t begin each writing session by sharpening twenty number-two pencils:

“I don’t think I ever owned twenty pencils at one time,” he told The Paris Review — but he did have his share of writing idiosyncrasies. He wrote standing up, facing a chest-high bookshelf with a typewriter on top, and on top of that a wooden reading board. First drafts were composed in pencil on onionskin typewriter paper laid slantwise across the board; when the work was going well, Hemingway would remove the board and shift to the typewriter. He tracked his daily word output on a chart — “so as not to kid myself,” he said. When the writing wasn’t going well, he would often knock off the fiction and answer letters, which gave him a welcome break from “the awful responsibility of writing” — or, as he sometimes called it, “the responsibility of awful writing.”Despite his notorious creative routine, later in life Henry Miller arrived at a kind of counter-moderation:

As he told one interviewer, “I don’t believe in draining the reservoir, do you see? I believe in getting up from the typewriter, away from it, while I still have things to say.” Two or three hours in the morning were enough for him, although he stressed the importance of keeping regular hours in order to cultivate a daily creative rhythm. “I know that to sustain these true moments of insight one has to be highly disciplined, lead a disciplined life,” he said.William Faulkner’s routine revolved heavily around his family and his wife, the woman for whose daughter he penned his only children’s book:

In the summer of 1930, the Faulkners purchased a large, dilapidated family estate, and Faulkner quit his job in order to repair the house and grounds. Then he would wake early, eat breakfast, and write at his desk all morning. (Faulkner liked to work in the library, and since the library door had no lock, he would remove the doorknob and take it with him.) After a noon lunch, he would continue repairs on the house and take a long walk or go horseback riding. In the evenings Faulkner and his wife would relax on the porch with a bottle of whiskey.Family life, in fact, dictated the routines of many creators. Though known for his uncompromising work ethic, Chuck Close shares:

I used to work at night, but when my kids were born I couldn’t just work at night and sleep during the day. So that’s when I started having a kind of regular, nine-to-five work schedule. And if I work more than three hours at a time, I really start screwing up. So the idea is to work for three hours, break for lunch, go back and work for three hours, and then, you know, break. Sometimes I could go back and work in the evening, but basically it was counterproductive. At a certain point, I’d start making enough mistakes that I would spend the next day trying to correct them.For all his deliberate pursuit of success, Alexander Graham Bell was also a family man:

As a young man, Bell tended to work around the clock, allowing himself only three or four hours of sleep a night. After his marriage and his wife’s pregnancy, however, the American inventor was persuaded to keep more regular hours. His wife, Mabel, forced him to get out of bed for breakfast each morning at 8:30 a.m. — “It is hard work and tears are spent over it sometimes,” she noted in a letter — and convinced him to reserve a few work-free hours after they dined together at 7:00 p.m. (He was allowed to return to his study at 10:00.)Despite his astounding creative output, from Ulysses to his lesser-known poetry to, even, children’s books, James Joyce once described himself as “a man of small virtue, inclined to extravagance and alcoholism.” And yet he followed a steady regimen:

He woke about 10 o’clock, an hour or more after Stanislaus had breakfast and left the house. Nora gave him coffee and rolls in bed, and he lay there, as Eileen [his sister] described him, “smothered in his own thoughts” until about 11 o’clock. Sometimes his Polish tailor called, and would sit discoursing on the edge of the bed while Joyce listened and nodded. About eleven he rose, shaved, and sat down at the piano (which he was buying slowly and perilously on the installment plan). As often as not his singing and playing were interrupted by the arrival of a bill collector. Joyce was notified and asked what was to be done. “Let them all come in,” he would say resignedly, as if an army were at the door. The collector would come in, dun him with small success, then be skillfully steered off into a discussion of music or politics.Picasso was decidedly a late chronotype:

Throughout his life, Picasso went to bed late and got up late. At the boulevard de Clichy, he would shut himself in the studio by 2:00 p.m. and work there until at least dusk.Beloved poet and cat-lover T. S. Eliot had to take a day job, which he actually enjoyed:

In 1917, Eliot took a job as a clerk at Lloyds Bank, in London. During his eight years of employment there, the Missouri-born poet assumed the guise of the archetypal English businessman: bowler hat, pin-striped suit umbrella rolled carefully under one arm, hair parted severely on the side.Writing in her journal in 1959, just four years before she took her own life, Sylvia Plath resolved:

[…]

Two days after his appointment there, he wrote to his mother, “I am now earning two pounds ten shillings a week for sitting in an office from 9:15 to 5 with an hour for lunch, and tea served in the office. . . . Perhaps it will surprise you to hear that I enjoy the work. It is not nearly so fatiguing as school teaching, and is more interesting.” He often used his lunch hour to discuss literary projects with friends and collaborators. In the evening he had time to work on his poetry, or to earn extra money from reviews and criticism.

From now on: see if this is possible: set alarm for 7:30 and get up then, tired or not. Rip through breakfast and housecleaning (bed and dishes, mopping or whatever) by 8:30. . . . Be writing before 9 (nine), that takes the curse off it.Much like his mentor, the tireless Thomas Edison, Nikola Tesla worked long and hard, but also knew how to recharge:

As a young apprentice in Thomas Edison’s New York office, Tesla regularly worked from 10:30 in the morning until 5:00 the following morning. (“I’ve had many hard- working assistants, but you take the cake,” Edison told him.) Later, after he had started his own company, Tesla arrived at the office at noon. Immediately, his secretary would draw the blinds; Tesla worked best in the dark and would raise the blinds again only in the event of a lightning storm, which he liked to watch flashing above the cityscape from his black mohair sofa. He typically worked at the office until midnight, with a break at 8:00 for dinner in the Palm Room of the Waldorf-Astoria hotel.

These dinners were carefully scripted affairs. Tesla ate alone, and phoned in his instructions for the meal in advance. Upon arriving, he was shown to his regular table, where eighteen clean linen napkins would be stacked at his place. As he waited for his meal, he would polish the already gleaming silver and crystal with these squares of linen, gradually amassing a heap of discarded napkins on the table. And when his dishes arrived—served to him not by a waiter but by the maître d’hôtel himself — Tesla would mentally calculate their cubic contents before eating, a strange compulsion he had developed in his childhood and without which he could never enjoy his food.

Edith Sitwell, whom Yeats held as the echelon of modern poetry, had a routine of legend:

Literary legend has it that Sitwell used to lie in an open coffin for a while before she began her day’s work; this foretaste of the grave was supposed to inspire her macabre fiction and poetry. The tale is probably false. What is certain is that Sitwell liked to write in bed, beginning at 5:30 or 6:00 a.m., this being “the only time when I can be sure of quiet.” “All women should have a day a week in bed,” Sitwell also remarked, and when she was engrossed in a writing project she would sometimes stay there all morning and through the afternoon—until finally, she said, “I am honestly so tired that all I can do is to lie on my bed with my mouth open.”In between penning extraordinary love letters, Honoré de Balzac followed an ambitious regimen:

Balzac drove himself relentlessly as a writer, motivated by enormous literary ambition as well as a never-ending string of creditors and endless cups of coffee; as Herbert J. Hunt has written, he engaged in “orgies of work punctuated by orgies of relaxation and pleasure.” When Balzac was working, his writing schedule was brutal: He ate a light dinner at 6:00 p.m., then went to bed. At 1:00 a.m. he rose and sat down at his writing table for a seven-hour stretch of work. At 8:00 a.m. he allowed himself a ninety-minute nap; then, from 9:30 to 4:00, he resumed work, drinking cup after cup of black coffee. (According to one estimate, he drank as many as fifty cups a day.) At 4:00 p.m. Balzac took a walk, had a bath, and received visitors until 6:00, when the cycle started all over again. “The days melt in my hands like ice in the sun,” he wrote in 1830. “I’m not living, I’m wearing myself out in a horrible fashion—but whether I die of work or something else, it’s all the same.”On the most eccentric end of the spectrum, we find Vladimir Nabokov — beloved author, butterfly-lover, no-bullshit lecturer, hater of clichés, man of strong opinions:

The Russian-born novelist’s writing habits were famously peculiar. Beginning in 1950, he composed first drafts in pencil on ruled index cards, which he stored in long file boxes. Since, Nabokov claimed, he pictured an entire novel in complete form before he began writing it, this method allowed him to compose passages out of sequence, in whatever order he pleased; by shuffling the cards around, he could quickly rearrange paragraphs, chapters, and whole swaths of the book. (His file box also served as portable desk; he started the first draft of Lolita on a road trip across America, working nights in the backseat of his parked car — the only place in the country, he said, with no noise and no drafts.) Only after months of this labor did he finally relinquish the cards to his wife, Vera, for a typed draft, which would then undergo several more rounds of revisions.But perhaps Leo Tolstoy, man of great wisdom, had perhaps the most emblematic relationship with the purpose of routine, professing in his diary in the mid-1860s:

I must write each day without fail, not so much for the success of the work, as in order not to get out of my routine.Daily Rituals features such beloved creators as Charles Darwin, Frank Lloyd Wright, Tchaikovsky, and Georgia O’Keeffe. But more than a mere voyeuristic tour of creative routines, what makes it particularly enjoyable is that Currey manages to take these seemingly superficial rotes and weave of them something so rich and representative of the human impulse for creativity, at once incredibly diverse and uniform in its compulsive restlessness.

Donating = Loving

Bringing you (ad-free) Brain Pickings takes hundreds of hours each month. If you find any joy and stimulation here, please consider becoming a Supporting Member with a recurring monthly donation of your choosing, between a cup of tea and a good dinner:

Bringing you (ad-free) Brain Pickings takes hundreds of hours each month. If you find any joy and stimulation here, please consider becoming a Supporting Member with a recurring monthly donation of your choosing, between a cup of tea and a good dinner:

You can also become a one-time patron with a single donation in any amount:

Brain Pickings has a free weekly newsletter. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s best articles. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.

Brain Pickings has a free weekly newsletter. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s best articles. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.

No comments:

Post a Comment